The following video made the rounds over the last week after being posted by He that shall not be named (or make interventions in governments around the world). In a dazzling contradiction of free market theory the man who meddles with democracy and with market forces posted this:

Ostensibly a celebration of the free market's invisible hand, the clip inadvertently exposes a far more troubling truth: the deliberate concealment of labor conditions within our everyday commodities. Friedman's repeated emphasis on his ignorance of the pencil's origins – the mines, the forests, the factories and the hands that shaped it – isn't a testament to market efficiency, but rather a obscuration of any potential exploitation. This ignorance, as we'll see, is the antithesis of genuine freedom.

Unfolding

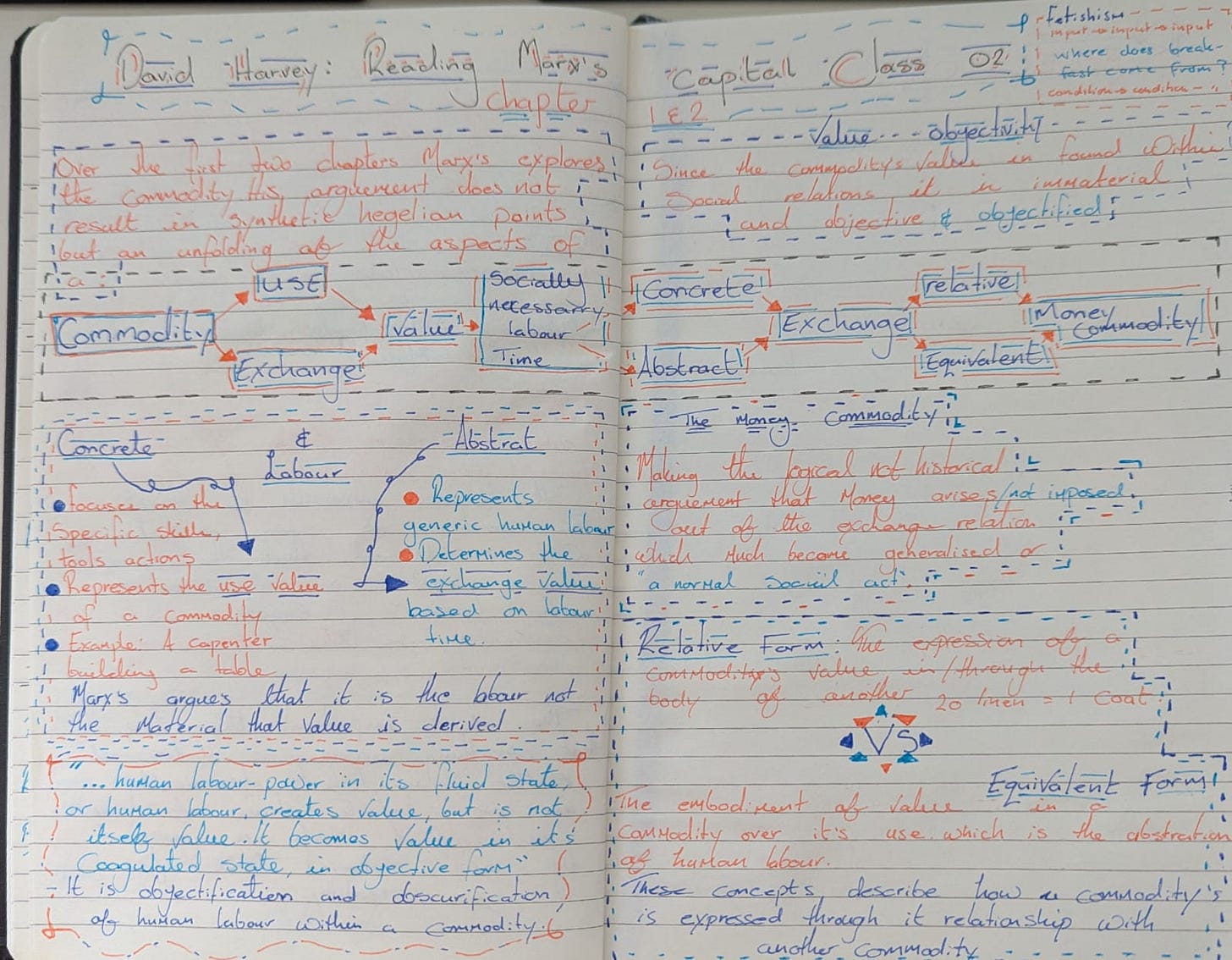

After being taken by the hand and led through the opening chapter of Capital by David Harvey here, we are able to begin to understand the value of what Marx set out to do. That is to show what is hidden within a commodity behind its price tag. As Milton does explain , our time is traded for the time of countless others in the purchasing of a pencil. Just as Marx argued the value of the commodity is found with the “socially necessary labour time” & the “social relations” (trade) in its making. Thus turning the immaterial value material and objectified.

While Friedman highlights the exchange of our time for the time of others embodied in the pencil, he conveniently omits the crucial details. What else is this unassuming object concealing? Well, as a start we can list: the conditions under which that labor is performed, the ratio of their exploited time to our purchasing power, the environmental cost of extracting raw materials – is this pencil a tool for creation or a harbinger of depletion? Without these answers, how can we possibly ascertain the true cost, the real value, of Friedman's seemingly innocuous pencil?

A Commodity Kink.

Marx termed this obscuring of social relations "commodity fetishism." This is the process by which the social and political structures underpinning production are masked, appearing instead as an inherent quality of the object itself.

Despite Friedman's attempt to tether his pencil directly to an abstract "free market," history reveals a far more complex tapestry of human exchange and production, unfolding across diverse political and economic systems. The very act of transforming social labor into economic value has been understood in fascinating ways throughout history, as Hanna Arendt illuminates.

Work & Labour

Hanna Ardent in her work The Human Condition defines “three fundamental human activities: labor, work, and action” here we will briefly consider and distinguish two: labour which supports the physiological processes of life, versus work as the reification of human thought into things in themselves. Labour being akin to a farmers “toil” and work the crafting of the tools used by the farmer.

Arendt traces the shifting dynamics between the public and private spheres and the evolving roles of those who labor and work. From commune member to slave to serf to factory worker. Her analysis reaches a critical point with the rise of industrialization, where the realm of consumption ("labor") increasingly encroaches upon the domain of craftsmanship and artistry ("work"). This shift, as Arendt observed, leads to a society where the triumph over necessity through the emancipation of labor paradoxically results in "mass culture" and a "universal unhappiness." This unhappiness stems from the imbalance between relentless consumption and the diminishing fulfillment found in objectified labor, alongside the unmet yearning for the natural rhythms of life.

Put simply the progress of our current human society has indeed freed most of us from the field, however most work has now been pulled into the realm of labour. Work has transformed into an ever-growing field of consumables which were once-upon-a-time long lasting items of use. Thus cheapening and shorting the value of our objectified labour, making us unhappy. Her prescient warning, even in 1968, pointed towards the dangers of a burgeoning "waste economy" – a consequence Friedman's "Lesson of the Pencil," delivered a decade prior, perhaps conveniently ignored in its simplistic celebration of an ontologically "free" market. By devaluing our labour we devalue ourselves and the fruits of our toil.

Reclaiming the Free in Free Market.

So, how can we, as contemporary consumers, genuinely claim to be free within a market where the intricate web of our interconnected labor is deliberately shrouded? If all the relevant information in a choice is clouded and hidden that choice can not be made in the light of consent In a system where the driving force isn't collective well-being but the accumulation of profit for a select few who control the means of production, is it any wonder that peeling back the layers of commodity production often reveals disturbing realities? Trapped in a cycle of supplying labor to fuel further production and consumption, we often find ourselves distracted by commodified luxuries, obscuring our own or others' exploitation.

To this Arendt reminds us that "Man cannot be free if he does not know that he is subject to necessity, because his freedom is always won in his never wholly successful attempts to liberate himself from necessity." Extending this dialectically, our choices in fulfilling those needs cannot be divorced from the conditions of their creation. Unlike (In her reading of) Marx's vision of transcending the labor process entirely, Arendt suggests that labor, being fundamental to life, cannot be eliminated.

We are held captive by our physiological and societal needs and unaware of the process that provide for those needs. History has shown trade is not exclusive to one economic model and that the teleological aims set the mode of that production process. In that light can we call for anything other than a transformation, prioritizing collective needs over the relentless pursuit of profit for the wealthiest – those who uncritically and in contradiction to their recent actions promote outdated notions of a purely "free" market as the Deus to save us from our ills.